Can an all-female anti-poaching unit stop wildlife crime in an African game preserve – without guns?

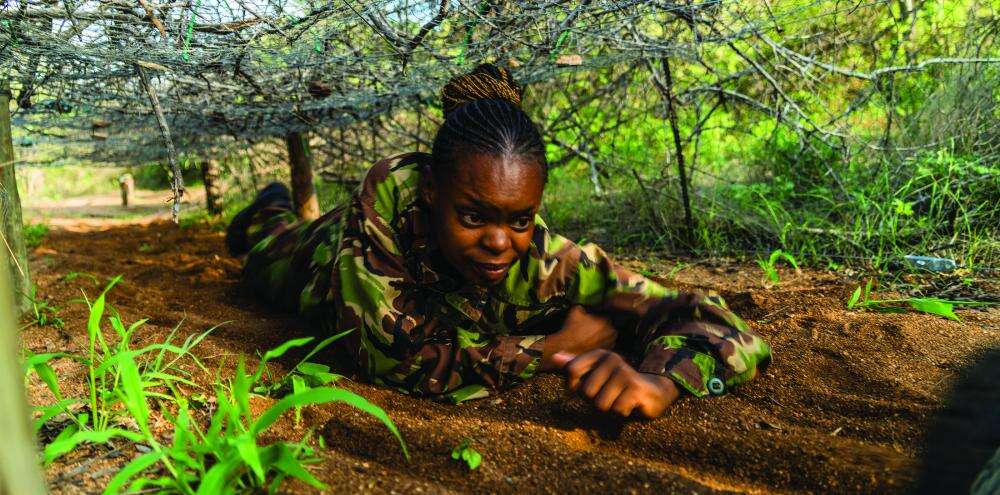

Dressed in a baggy green camouflage uniform and black work boots, long ponytail swinging against her back, Tsakane Nxumalo, 26, and her partner Naledi Malungane, 21, stride alongside an elephant-proof electric fence that is 7 feet high and nearly 100 miles long. The potent, honey-like odor of purple-pod cluster-leaf trees hangs heavy in the humid summer air, while overhead a yellow-billed hornbill swoops to perch on the skeleton of a dead leadwood tree. Nxumalo and Malungane are members of the Black Mambas Anti-Poaching Unit. Named after a snake that is native to the region and long, fast, and highly venomous, the Mambas strive to protect the animals of the Balule Nature Reserve within Greater Kruger National Park, a South African wilderness that is about the size of Israel.

Nxumalo and Malungane, who both grew up near the unit’s headquarters but only got to know each other since they became Mambas, are checking, as they do every day of their 21-day shift, for breaches in the fence. Mostly this entails collecting rocks to shore up the places where animals such as warthogs and leopards have tried to burrow their way under, but periodically they come across a spot where humans have cut the fence to hunt animals for bushmeat or, worse, poach rhinos for their horns.

In 2013, when the first Mambas began patrolling the reserve, they quickly discovered that rhino poaching was only part of the problem. The park was also losing hundreds of animals of all species to snares every year. “It was embarrassing,” recalls Craig Spencer, 48, as he sits by a bushveld braai (barbecue) and talks over the calls of a nearby hyena. A maverick South African conservationist, he was head warden of Balule, a private animal preserve. “I should have known what was happening under my nose. It took the Mambas to show me what was going on.”

White rhinos have been hunted almost to extinction in Africa. Of the continent’s 18,000 remaining white rhinos, nearly 90 percent are in South Africa, the species’ last best hope. Kruger is home to by far the biggest white rhino population, as well as about 300 of the world’s 5,600 remaining black rhinos.

The rhinoceros horn is prized in some countries, used as a traditional medicine and a status symbol. According to the Wildlife Justice Commission, a horn fetches an average of $4,000 per pound in Africa, and as much as $8,000 per pound in Asia; given that a set of white rhino horns typically weighs 11 pounds, it’s worth between $44,000 and $88,000. South Africa’s per capita income is about $5,000 per year and its pre-COVID-19 unemployment rate was about 29 percent. Therefore, a rhino, sadly, is a tempting target. In 2017, poachers killed more than 500 rhinos in Greater Kruger National Park, including 17 in Balule.

This story was written by Nick Dall Photography by Bobby Neptune originally appeared in the April 2022 issue of Rotary Magazine: To read the full story go to https://www.rotary.org/en/white-rhinos-and-black-mambas